The Transcendence of Time, the gallery’s fourth solo exhibition with conceptual artist Nate Young.

Through this new body of work, Young mines his own family archives to explore and question the nature of identification, history, and the significance of ritual as a means to instill authority.

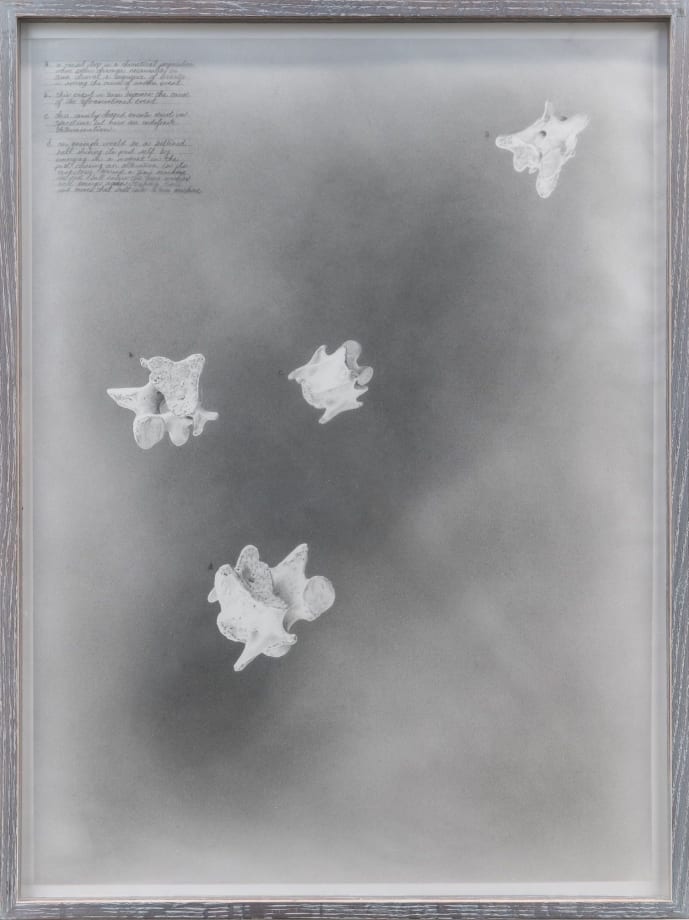

The Transcendence of Time allows for a deeper investigation into excavated bones thought to be from the horse that once carried the artist’s great-grandfather from the South to the North during the Great Migration, a personal narrative illuminated by the larger history of US race relations and the movement of black bodies. In this continuum of work, Young now considers the impetus of the bones through the lens of science and philosophy, exploring their ability to offer clues and insights to his family’s unique journey to identity, while also connecting to a more universal narrative.

Essay

by Nyeema Morgan and Mike Cloud

June 2020

The quiet incantations of Nate Young’s works— sensual and ethereal graphite drawings and skillfully crafted wood sculptures resembling humble furniture— take on profound significance during our current global pandemic and nationwide civil unrest. To be in the presence of, and to think about, Young’s work while overwhelmed by the relentless bombast of American political rhetoric is to be suspended in time and space where contemporary life and history are folded on themselves, where the body and the spirit are distinguished yet interdependent and occasionally at odds. This momentary suspension feels necessary.

How long can we endure, and be complicit in, oppression and systemic inequities? The history of American capitalist ideology, rooted in white supremacy, espouses prosperity and liberty by divine right— a political idea rather than a religious one evoked as a foundation of inalienable rights for “free men”, the idealized citizen, the autonomous being at the center of all social, economic and political life, masters of their own unbridled destiny.

“If you have never been deprived of your liberty, as I was, you cannot realize the power of that hope of freedom, which was to me indeed, an anchor to the soul both sure and steadfast.” - Henry “Box” Brown, 1849, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown.

The objectification of people relegates them to a taxonomy of objects. As such, objectified “others” are pushed from the empathetic center of human subjectivity and are understood as being devoid of free will to lord political power. Through this oppressive logic, the objectified others’ participation in the world is merely driven by a force that occupies them. In cultural folklore, objects (or sculptures) are possessed—occupied through enchantment by a particular spirit. In various identity mythologies, this spirit may be characterized as deceit, greed, hate or lust for example. The objects serve as bodily vessels for what was known in Ancient Egypt as ‘Ba’, so that the spirit may interact with the world of other things—totems, sacred relics, Frosty the Snowman, golem, Ouija boards, the Amityville House. Within the identity mythology of the other is the mysticism of female seductive enchantment, the “magical Negro”, indigenous people’s intuited communion with nature and so on. Identity, as an archetype, is separate from the objectified living beings that labor beneath it.

The mythologies at the center of Young’s work are both aesthetic and material, related to the artist’s own parentage, faith and legacy. His uncanny, rarified objects, liturgical in appearance, are reminiscent of reliquaries, tables and altars, and are situated between craft tradition and the esotericism of sculptural art objects. A number of provoking references can be gleaned from Young’s works, including Hegel’s master-slave dialectic, metaphysical paradoxes implied by the possibilities of time travel and the subject of fugitivity. Representative of the latter is the extraordinary story of Henry “Box” Brown, who in 1849 escaped slavery by shipping himself north in a self-carpentered wooden crate (Brown later became a professional stage magician).

Brown’s vessel of escape and the peril of his journey also share a metaphoric relationship to the Judaic “sukkah”, a temporary shelter originally constructed by the Israelites as they fled from their Egyptian masters. Paradoxically, the modern evocation of sukkahs are joyous symbols of human frailty and dependence on providence. When dispossessed European Jews immigrated to the United States in the early 20th century, they found new possibilities for cultural mobility and status. Placing a piano in the sukkah during the holy week of Sukkot was one way of expressing that newfound hope and faith in possession and accomplishment. Identity, being a purely subjective possession, often functions for the faithful as a transcendence beyond material possessions. But by the same token, the sacred heirloom (aged, battered, and repaired as a material body in its own right) can accomplish a transcendence of its own beyond identity and spirit. While the Hebrew teacher taught the maintenance of a static identity, the piano teacher taught cultural mobility, garnering higher esteem than the Hebrew teacher.

Young’s ruminations on mobility and his paternal lineage, characterized by depictions of Black masculinity, places the sukkah within the heirloom, so to speak. It locates frailty at the heart of his apparently stolid constructions, functioning as an armor that contains both a corpse (a horse/ male ancestor bone) and a ghost (the holographic reflection of that bone). Like a tiny sukkah carefully placed within an exquisitely crafted Steinway, Young’s recent work radically short-circuits the relationships between frailty, stolidity and inheritance, through the aesthetics of the heirloom and the archetypal narrative of Black masculinity, dispossessed of everything except his spirit and his flesh. The character in Young’s narrative is one of his very own ancestors, his great- grandfather— a horseman, an unrewarded genius, an unpitied fugitive and an unrepentant philanderer. Young limits his sensual depictions of his horseman/ancestor to often half-visible handwritten texts. He denies us the familiar and welcome aesthetic charge of Black male flesh and fills the cavity that denial creates with a pastoral aesthetic (in the liturgical rather than natural sense). The mundane, liberatory, handwritten text, dark, somber wood finish, bespoke, slightly idiosyncratic dimensions and relentlessly erect specificity of sculptural form place three distinct spirits in a fruitful counter suspension. The first of these spirits is the radical political spirit of Black masculinity represented by the narrative of his ancestor/genius in his oppression, flight and philandery. The second is the spirit of the artist’s own expressive inner life as the creator of the work and its meaning. The last is the spirit of our communal God and his/her/its call to submission through craft, stability and decorum. That final spiritual call is the subtext in this text-heavy work. The work’s sophisticated aesthetics, through stolid craftsmanship and monkish minimalism, conjure Black pastorship as a foil to the rakish horseman. Both the pastor and the horseman are, after all, possessed by a spirit: the social spirit of religious discipline and the political spirit of racial survival.

Great works of art seem to transcend being merely the personal work of a particular individual and become culture works in which many different individuals find themselves represented in different ways. Young submits to, embraces and otherwise reconciles himself to the many spirits that haunt our shared political, social and economic moment. Through his delicate touch, deft associations and muscular craftsmanship, Young’s poetically resonant work constitutes a profound contemporary text that folds itself through the contradictions of time, space and identity that we all find ourselves laboring beneath.